When visiting some of the world’s most beautiful cities, it’s easy to overlook the eerie secrets lying beneath the bustling streets. Yet, hidden below these iconic locations are catacombs—mysterious underground chambers that tell stories of life, death, and ancient practices.

Take Paris, for example. Known globally as the City of Love, it could just as easily be dubbed the City of Bones. Beneath the romantic boulevards and historic landmarks lie the remains of six million Parisians. These haunting caverns, carved into the earth, form one of the largest ossuaries in the world. Similarly, Rome hides over 40 ancient catacombs under its historic streets. However, the fascination with underground tombs extends far beyond France and Italy. Countries like Malta, Peru, and Tunisia also house crypts that offer a chilling glimpse into the past.

A Glimpse into the Origins of Catacombs

The history of catacombs dates back thousands of years. Some of the oldest examples can be found in Rome, where these crypts emerged during the 1st century. Originally built by Jewish families, they provided a solution to Roman laws that prohibited burials within city walls. These underground tombs offered a sacred resting place for loved ones while adhering to the regulations of the time.

By the 2nd century, Christians began using catacombs as burial grounds. During a time when Christianity was outlawed in Rome, these hidden chambers beneath privately owned land became a haven where believers could bury their dead without fear of persecution. According to historical accounts, many of these early Christian catacombs date from the 2nd to the 4th centuries.

While most catacombs were constructed underground, others, like the Lycian tombs in Turkey, were carved directly into natural rock formations, often mountainsides. This technique, dating back to the 4th century, demonstrates the ingenuity of ancient builders. As Christianity became Rome’s official religion by the end of the 4th century, the practice of underground burial gradually faded. Above-ground cemeteries replaced hidden tombs, leaving many ancient catacombs forgotten for centuries.

The Paris Catacombs: A City’s Unique Solution

Fast forward to the 17th and 18th centuries, Paris faced a unique burial crisis. As the city’s population boomed, its cemeteries became overcrowded, creating a series of public health challenges. The situation grew dire when the stench of decaying bodies began to overwhelm nearby neighborhoods, even driving away customers from perfume shops, according to historical accounts.

The problem reached its peak in 1780 when heavy rains caused a cemetery wall to collapse, unleashing a wave of decomposing remains into the streets. Desperate for a solution, city officials turned to the network of ancient quarries beneath Paris. These tunnels, once used for mining, became a practical solution for relocating the dead.

In 1786, the process of transferring bodies began. Over the next 12 years, workers transported the remains of millions from overcrowded cemeteries like Les Innocents into the underground tunnels. These crypts, now famously known as the Paris Catacombs, house bones dating back over a millennium.

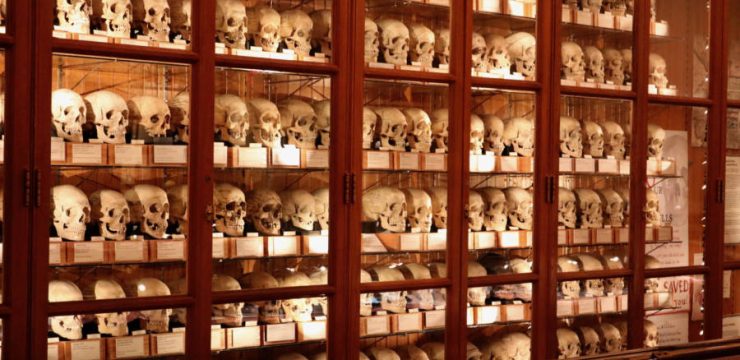

Today, visitors can explore a small portion of this vast underground network, where walls are meticulously lined with skulls and femurs. At the entrance, a foreboding sign greets visitors: “Arrête, c’est ici l’empire de la mort!” (“Stop! This is the empire of death!”).

Rediscovering Ancient Crypts

While some catacombs, like those in Paris, have been accessible for centuries, others remained hidden for much longer. Their rediscovery often involved a combination of curiosity, luck, and archaeological determination.

One notable example is the work of Antonio Bosio, an Italian archaeologist who became known as the “Columbus of the Catacombs.” In 1593, Bosio ventured into a Roman tunnel whose entrance had been opened but remained unexplored. What he uncovered was a labyrinth of underground tombs, untouched for centuries. His findings shed light on the extensive burial practices of ancient Rome.

Centuries later, rediscoveries continued to astonish the world. In 2001, the second-largest ossuary in Europe was unearthed during renovations at the Church of St. James in the Czech Republic. This ossuary in Brno, filled with the remains of 50,000 individuals, had been forgotten for generations. Today, it stands as a testament to the intricate and often macabre history of human burial practices.

The Global Legacy of Catacombs

Beyond Paris and Rome, catacombs and ossuaries can be found across the globe. In Peru, the San Francisco Monastery houses chilling underground crypts, where rows of bones are displayed in geometric patterns. Malta’s St. Paul’s Catacombs and Tunisia’s early Christian crypts also offer glimpses into the burial customs of ancient civilizations.

Even in modern times, catacombs captivate the imagination. These subterranean spaces not only serve as historical records but also inspire countless myths and legends. Some, like the Ossuary of Verona in Italy, are strikingly decorated with human skulls, creating an atmosphere that is both haunting and reverent.

What Lies Beneath the Surface

For centuries, humans have stored their dead in underground chambers, building walls of bones and decorating tunnels with skulls. These practices reflect cultural beliefs about death, reverence for the deceased, and practical solutions to space constraints.

The fascination with catacombs endures, raising questions about what other secrets might lie hidden beneath the earth. While many ancient crypts have been uncovered, countless others remain lost to time. The question is not if more catacombs will be discovered, but when.

Whether it’s the iconic Paris Catacombs, the rediscovered ossuary in Brno, or the ancient Roman burial tunnels, these eerie chambers continue to intrigue and unsettle those who dare to explore them. Beneath the surface of some of the world’s most vibrant cities lies a silent reminder of the past—a chilling yet fascinating glimpse into humanity’s relationship with death and the afterlife.